Similar to the infographics I created to celebrate World Orangutan Day and Manatee Appreciation Day, I’ve put together some fun facts about everybody’s favourite birds on World Penguin Day!

Into the Mist

Trekking with the critically endangered mountain gorilla in Rwanda

During the past 18 months, I have been on an incredible journey throughout the Asian and African continents that has included many wonderful encounters with wildlife. From experiencing my first safari to diving with great white sharks, I have been very lucky. One might think that such a lifestyle would eventually grow wearisome, however, my desire to witness wild animals in their natural habitat grows stronger with every experience. Fortunately, I was able to further indulge my passion when I relocated to the small east African country of Rwanda last December. Aptly named “The land of a thousand hills”, Rwanda boasts a wide array of flora and fauna to be marvelled at. It is best-known among wildlife enthusiasts and conservationists for its high concentration of colourful birds and endangered primates.

Since moving to Rwanda, I have taken advantage of the many wildlife watching opportunities that this great land has to offer, visiting Akagera National Park and also travelling to the beautiful Nyungwe Forest to trek chimpanzees. There really is no other way to observe such spectacular animals than in their natural environment, as their behaviour and interactions with one another are in stark contrast to that when behind bars in a zoo. They were both truly amazing days that I will never forget. However, the magnitude of these experiences was overwhelmingly dwarfed by that of last weekend’s gorilla trekking.

Rwanda is one of three countries that are home to the critically endangered mountain gorilla. Surprisingly, it was as late as 1902 when these graceful beasts were first discovered by scientists, and since that day, mountain gorilla populations have been under serious threat of extinction. Poaching, habitat loss, disease and warfare have all contributed toward their decline and in 1981, it was estimated that as little as 254 mountain gorillas remained. Perhaps most horrifying of all, silverbacks were killed for their heads and hands which were sold to collectors. In addition, many protective parents were killed when their babies were taken away to be exhibited in zoos all over the world. Thankfully, recent years have seen large conservation efforts which have helped to ensure that these creatures have not become mere museum memories. It is now believed that there are at least 880 individuals wandering the hills of Rwanda, Uganda and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

A large contributing factor toward the recovery of the mountain gorilla population has been through ecotourism. Wildlife enthusiasts from all corners of the globe travel to eastern Africa to witness the glorious spectacle of the great apes roaming freely in their natural habitat. Visitors must book permits weeks in advance, as the number of people allowed to view the gorillas each day is very limited. Encounters with our primate cousins are also restricted to a single one-hour session per day, and so the $750 fee per permit may seem astronomical to some. In hindsight, I cannot put into words how insignificant the cost turned out to be.

I left the comforts of my hotel room at around six o’clock on a misty Sunday morning and shortly after I arrived at the base camp where I was to learn which gorilla family I would be trekking. My guide announced that we had been assigned to the Ntambara (fighters) group – a band of 16 individuals. I met with the six other trekkers who had been assigned to the same group and we all briefly introduced ourselves to one another. Soon after, we excitedly jumped into a jeep and headed off toward the foot of the mountain of which the Ntambara group were located. Around half an hour later we arrived at our destination, climbed out of the jeep and began our ascent up into the mist.

During the relatively effortless hike toward the national park, we made a few stops where our guide taught us about some of the flora in the area. It was interesting to learn about the local vegetation and it helped to make the 45 minutes it took to reach the border of the national park go by quickly. Before crossing through the park’s perimeter, our guide gave us instructions on how to behave when we came across the gorillas and ways in which to react to different situations that may occur. Shortly after, he received confirmation on his two-way radio that the trackers had located the Ntambara group. They continuously updated him on the location of the gorillas and it became clear to all in the group that he knew exactly how far they were positioned from us. My fellow trekkers and I were keen to learn how long we would be hiking before we found the gorillas to which our guide teasingly responded “less than five hours”.

As we climbed over the cobblestone wall which separated the surrounding farmland from the forest, it became very apparent that this was going to be an arduous trek. It had rained continuously throughout the past few days and we all found ourselves ankle deep in the thick sodden soil. We hiked for around half an hour on the main trail before we met with one of the trackers and veered off onto a completely new route. I began to grow excited as it became obvious that we were in close proximity to the Ntambara group.

We continued through the thick lush green forest for around 15 minutes before happening upon two other trackers who instructed us to stop. Within seconds I heard a noise that sounded very similar to that of bongo drums and instantly I recognised that it was the sound of a gorilla beating its chest. I could feel my eyes growing wider and an adrenaline rush like I had never felt before as the realisation set in that we were about to be acquainted with one of the greatest animals to roam the planet.

As we approached the area from which we had heard the chest-beating, a large and imposing silverback emerged from a nearby bush and slowly moved his way toward us. Members of our group began frantically throwing themselves off the trail to allow him the space to pass through. I had not imagined that I could have been within a metre or so of a wild animal with such immense power and lived to tell the tale. As he unhurriedly distanced himself from us, everybody breathed a sigh of relief as if they had believed that a strictly herbivorous creature had recently acquired a taste for human flesh. We continued on to discover more members of the Ntambara group which included two females, a juvenile and an even larger Silverback feeding in a small opening.

We spent the next hour almost entirely in silence as we observed the gorillas moving in all directions around us. As we gradually moved our way around the tranquil forest, we managed to locate other members of the Ntambara group including a few amusing adolescents. Unoriginal as it may be, though, the toddler provided the most enjoyment for me personally. Before encountering the gorillas we had been instructed that should any of the infants approach us, we should make every effort to back away in order to ensure that no complications would arise with their extremely protective parents. One of the hardest things I’ve ever had to do was distance myself from the juvenile that seemed intrigued by a fellow trekker and I. Nevertheless, I felt incredibly privileged to have been within a few feet of the curious little chap.

The enhanced elation I felt in contrast to my previous encounters with wildlife was undoubtedly down to the fact that I had spent less time behind the camera lens and more time simply observing. From previous experiences I have learnt that photographs are no substitution for enjoying the moment as it happens.

I honestly cannot find the words to express the wonder of sharing a short moment in time alongside such immensely powerful and magnificently intelligent animals. Magical perhaps, but the only way that one can really understand the euphoria surrounding even the briefest encounter with such glorious beings is to experience it for themselves.

This article was originally published by Youth Time International Magazine

(The Real) Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them - Great Apes

Dr. Jane Goodall’s birthday seemed like a good time to introduce some of our closest living relatives – the great apes - along with tips on where to best see them in the wild in this latest version of (The Real) Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them.

Western Gorilla

Divided into two sub-species, the Western Lowland Gorilla (Gorilla g. gorilla) and the Cross River Gorilla (Gorilla. G diehli), can be found in the tropical and subtropical broadleaf forests of West Africa. Western Lowland Gorillas are smaller and lighter than all other gorilla subspecies and are also the most widespread. They inhabit Africa’s densest and most remote rainforests, making it hard for scientists to make accurate estimates on their overall population. However it is thought that there are somewhere around 100,000 individuals, making them the most numerous of all the subspecies. The Cross River Gorilla is the world’s rarest great ape and is restricted to a small area of montane rainforest on the border of Cameroon and Nigeria. Their population is estimated at only around 250-300 individuals.

Eastern Gorilla

As with the Western Gorilla, the Eastern Gorillas are made up of two subspecies – the Eastern Lowland Gorilla, or, Grauer’s Gorilla (Gorilla. b. graueri) and the Mountain Gorilla (Gorilla. b. beringei). The Grauer’s Gorilla is the largest of all the gorilla subspecies and can be found only in the rainforests of eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. Research suggests that Eastern Lowland Gorillas occupy only around 13% of their former geographic range and that their population has declined from 17,000 individuals in the 1990s to just 4,000 today. Their closely related cousins, the Mountain Gorilla are slightly smaller and sport longer coats of hair. Made famous by Diane Fossey and the film Gorillas in the Mist, Mountain Gorilla populations have steadily increased in the last few years thanks to dedicated conservation initiatives. Once on the brink of extinction, their numbers are at around 880 individuals today. Only three countries are home to the magnificent Mountain Gorilla, namely Rwanda, Uganda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Chimpanzee

One of our closest living relatives, the Chimpanzee share about 96% of our DNA. Scientists have divided the species into four separate subspecies based on differences in appearance and distribution (Western chimpanzee (Pan. t. verus), Central chimpanzee (Pan. t. troglodytes), Eastern chimpanzee (Pan. t. schweinfurthii), and Nigeria-Cameroon chimpanzee (Pan. t. ellioti)). It is estimated that the wild population of all subspecies together ranges between 150,000 to 250,000 individuals with the Central Chimpanzee being the most numerous and Nigeria-Cameroon Chimpanzee the least. Collectively, they are the most widespread species of all great apes, though their distribution is still considerably smaller and fragmented than it once was. The largest remaining populations occur in central Africa, but the best places to trek chimpanzees are Mahale Mountains National Park in Tanzania, Kibale National Park in Uganda and Nyungwe Forest in Rwanda.

Bonobo

The Bonobo is arguably our closest living relative yet we still know relatively little about them. Very similar in appearance to the chimpanzee, they are also known as pygmy chimpanzees due to the fact they are generally smaller in size. Other distinguishing features include jet black faces with red lips and a prominent tail tuft. Aside from physical characteristics, Bonobos exhibit remarkably different social behavior from chimpanzees. In particular, they are a far more peaceful species than their close cousins who have been known to kill and even eat one another. Restricted to the low-lying basin of Equatorial Africa and found only in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, it is estimated that around 10,000 to 20,000 bonobos are left in the wild. However, data has revealed that their population is fragmented and decreasing. For the best chances of seeing wild Bonobos, head to Salonga National Park.

Sumatran Orangutan

Until very recently, the Sumatran Orangutan was considered the most endangered of two-subspecies with only around 14,600 individuals left in the wild. That was until a new and even more vulnerable to extinction subspecies was discovered on the very same Indonesian island of Sumatra. They are almost exclusively arboreal and can be found living among the trees of tropical rainforests where they feed upon figs and other fruits. Sumatran Orangutans once ranged across the entire island of Sumatra and even further south into Java, however, the nine remaining populations now only inhabit the northerly provinces of North Sumatra and Aceh. For tourists wishing to see the Sumatran Orangutan in the wild, their best bet is to visit Gunung Leuser National Park.

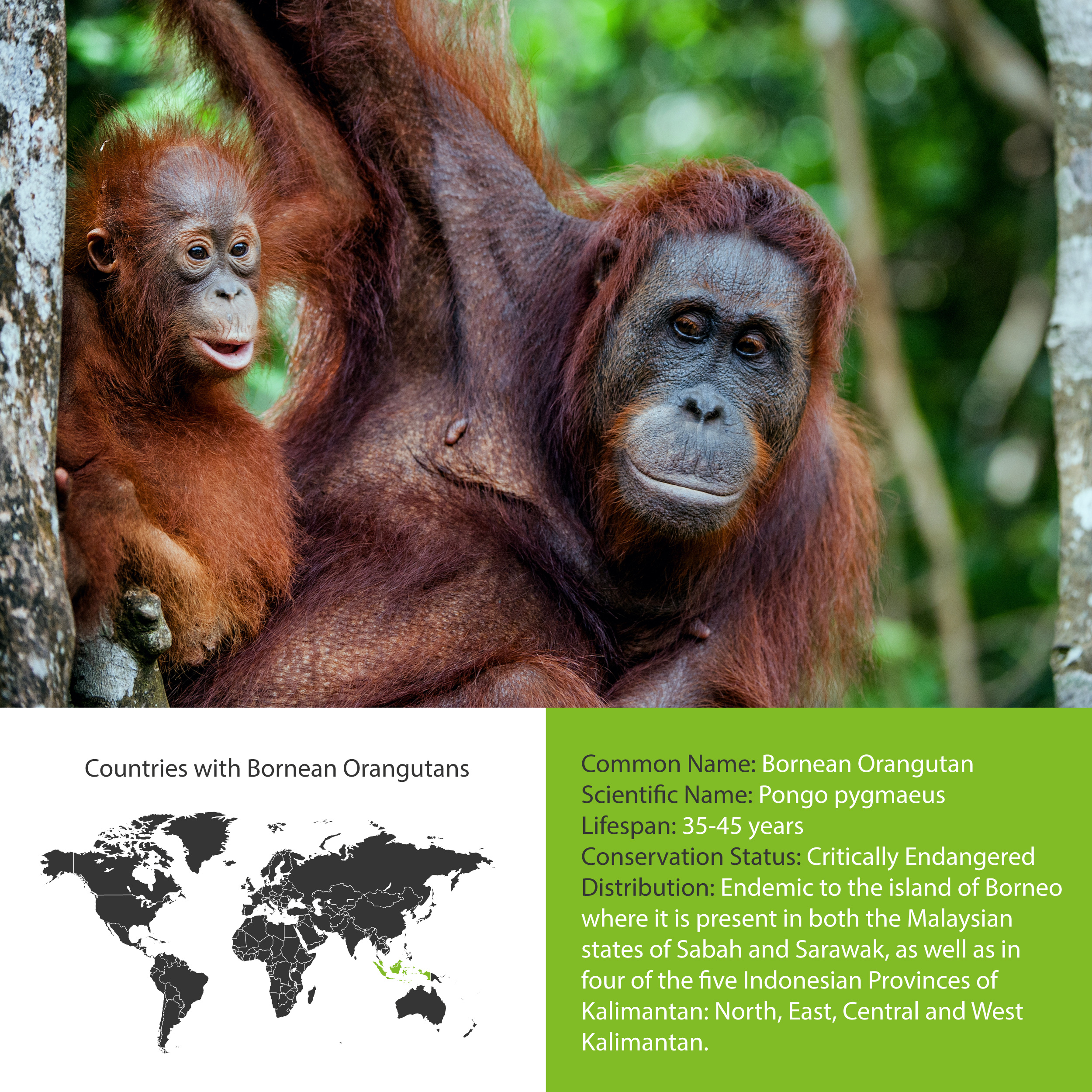

Bornean Orangutan

With an estimated 104,700 individuals living in the three countries (Brunei, Indonesia and Malaysia) which make up the island of Borneo, the Bornean Orangutan is easily the most numerous of the three subspecies. Despite their large population, they are still considered as critically endangered on the IUCN red list because of their rapid decline due to habitat loss and illegal poaching. In fact, their populations have declined by more than 50% over the past 60 years owing to the fact that forests and swamps that were once their homes are being torn down to make way for palm oil plantations and logging. Scientists have divided the Bornean Orangutan into three subspecies (Central Bornean Orangutan, Northwest Bornean Orangutan and Northeast Bornean Orangutan) with the former having the largest population. Arguably the best place to spot the “old man of the jungle” in its natural environment is in the Danum Valley.

Tapanuli Orangutan

Announced in late 2017 as a new subspecies of orangutan, the Tapanuli Orangutan is now considered to be the rarest of the great apes alongside the cross river gorilla with an estimated 800 or fewer individuals. They were discovered first in 1997, but following extensive research were determined as a new third species based on morphological and genomic evidence. The Tapanuli Orangutan is believed to have been isolated from its close relatives around 10,000 to 20,000 years ago. They occupy and are endemic to an area of 475 square mile upland forest in the Batang Toru Ecosystem situated in northern Sumatra.

All photos are Shutterstock. Graphics by Leigh Woods.